U.S. Forest Service officials have extended an emergency order that restricts access to caves and abandoned mines on lands in Colorado, Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska and Kansas. But some Colorado cavers are criticizing the approach taken by the federal agency.

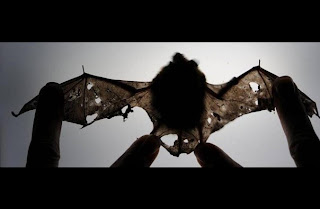

The goal of both groups is to curb the spread of White Nose Syndrome, a deadly disease that’s killed 5.5 million bats in eastern and southern states.

“Western Oklahoma is actually the furthest west that it's been detected, and actually it’s the fungus that causes White Nose Syndrome that has been confirmed,” says USFS Spokesperson Janelle Smith.’

With the disease on Colorado’s doorstep, Smith says the U.S. Forest Service decided to extend an emergency blanket closure order for a third year in a row. The move isn’t popular with some Colorado cavers, who favor targeted closures on U.S. Forest land.

“The caving community doesn’t feel it’s the most effective approach,” says Derek Bristol, chair of the Colorado Cave Survey.

Bristol says closing all 30,000 abandoned mines and hundreds of caves unnecessarily cuts off access for members of his group. Instead, he favors specific closures of caves that bats are known to use for activities such as hibernation and maternity roosts.

“The caving community could be an ally in helping to enforce closure of sensitive sites,” says Bristol. “But since they’ve chosen to go the route of blanket closure orders of all caves they’ve really alienated the caving community by doing that.”

The U.S. Forest Service is working with national groups like Alabama-based

National Speleological Society and Kentucky-based Cave Research Foundation. Active members of both groups can get exemptions from the closure orders. Gaining access to the caves will still involve some paperwork.

Meantime, Spokesperson Janelle Smith says other groups and individuals can also apply for exemptions to enter caves. Exactly what that process will look like is unfolding right now.

“We definitely are requiring written permission from the Forest Supervisor to authorize an activity that’s approved. People who get that permission will be able to enter the caves,” she says.

Smith says the agency will focus on approving visits that add to scientific understanding of the disease. Researchers are still trying to figure out how to hault the spread of White Nose Syndrome.

Source: KUNC