The Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) confirmed April 2 that WNS had been found on three bats in two caves, exactly two years after the fungus was first observed there. “White-nose syndrome in Missouri is following the deadly pattern it has exhibited elsewhere,” Mollie Matteson, a bat specialist with the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD), said in a prepared statement. “First the fungus shows up on a few healthy bats. A couple of years later, the disease strikes. And if the pattern continues, we can expect that in another few years, the majority of Missouri’s hibernating bats will be dead.”

The names and locations of the Missouri caves, which are closed to the public, were not disclosed in order to limit the chance of humans accidentally stressing the remaining bats. “Disturbing bats in caves while they roost or hibernate can increase their stress and further weaken their health,” MDC bat biologist Tony Elliott said in a prepared statement.

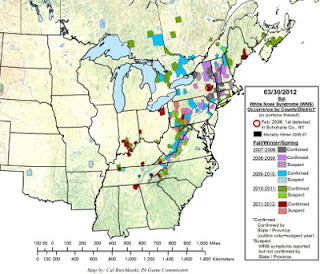

WNS has, in just the past few weeks, been confirmed in Delaware, Alabama, Maine’s Acadia National Park, and Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee and North Carolina. The disease has also spread to new locations in Kentucky, Ohio and Indiana. The fungus appears to be transmitted from bat to bat, or by humans visiting bat caves. The disease threatens four endangered species: Indiana bats (Myotis sodalis), which have been killed by WNS: gray bats (Myotis grisescens), on which the fungus has been found; and the Virginia big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus) and the Ozark big-eared bat (Plecotus townsendii ingens), both of which live in areas affected by the fungus.

As the WNS name suggests, the fungus first manifests as white fuzz on the faces of infected hibernating bats, but according to the U.S. Geological Survey’s Fort Collins Science Center, the real damage may come when it spreads to bats’ wings: “Wing membranes represent about 85 percent of a bat’s total surface area and play a critical role in balancing complex physiological processes. Healthy wing membranes are vital to bats, as they help regulate body temperature, blood pressure, water balance and gas exchange—not to mention the ability to fly and to feed.” According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), bats with WNS behave uncharacteristically, such as flying outdoors during the cold winter months or gathering at cave mouths when they should be hibernating. Such behavior could cause bats to burn off their winter fat reserves, leaving them susceptible to freezing or starvation.

As the WNS name suggests, the fungus first manifests as white fuzz on the faces of infected hibernating bats, but according to the U.S. Geological Survey’s Fort Collins Science Center, the real damage may come when it spreads to bats’ wings: “Wing membranes represent about 85 percent of a bat’s total surface area and play a critical role in balancing complex physiological processes. Healthy wing membranes are vital to bats, as they help regulate body temperature, blood pressure, water balance and gas exchange—not to mention the ability to fly and to feed.” According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), bats with WNS behave uncharacteristically, such as flying outdoors during the cold winter months or gathering at cave mouths when they should be hibernating. Such behavior could cause bats to burn off their winter fat reserves, leaving them susceptible to freezing or starvation.Although WNS and the Geomyces destructans fungus appear to have no effect on humans, their potential impact on human health is troubling. As the bats disappear, growing insect populations could spread disease or devastate agricultural crops. Citing just the most recently afflicted state as an example, Missouri’s 775,000 gray bats eat more than 223 billion bugs each year, according to the CBD. Although the potential effect on U.S. agriculture has not yet been felt, a recent study found that the loss of North American bats could lead to agricultural losses of more than $3.7 billion per year.

Research into WNS is ongoing, and there are a few small rays of hope. Some European bat populations that have come in contact with the G. destructans fungus appear to be resistant to it, and in fact some scientists theorize the fungus may have originated in Europe and recently been carried to the New World by humans. In addition, a few small populations of little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) in Pennsylvania and Vermont also appear to have remained healthy despite three years of contact with the fungus, for as-yet-unknown reasons.

For more information on WNS, visit the FWS resource page about white-nose syndrome, including their safety guide for cavers, or follow FWS’s White-Nose Syndrome in Bats page on Facebook. The CBD’s Save Our Bats campaign offers several actions people can take to encourage government efforts to help slow the spread of the disease.

Photos: White-nose syndrome on a little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) taken March 30, 2012, in Missouri, courtesy of Missouri Department of Conservation. Map of white-nose syndrome by county/district as of March 30, 2012. Courtesy of Cal Butchkoski, Pennsylvania Game Commission, via the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Source: Scientific American