The Book Cave Pearls of Meghalaya, Volume 1, Pala Range and Kopili Valley is now available – at least for British and Irish cavers, who can get it via Fraser or the GSG or via [email protected]

The Book Cave Pearls of Meghalaya, Volume 1, Pala Range and Kopili Valley is now available – at least for British and Irish cavers, who can get it via Fraser or the GSG or via [email protected]Cavers on the Continent will have to wait for another two weeks – the books are still on a ship bound for Hamburg.

Short description:

It is an A4 sized hardback of 265 pages in full colour and covers the exploration of caves in the Pala Range and Kopili Valley. There are chapters on Meghalaya, on the 2010, 2011 and 2012 expeditions in that area, and also on the geology, subterranean ecology, spiders and bats. The second half of the book is devoted to cave descriptions each with survey and photographs plus a list of minor caves and other sites of speleological interest. An unexpected (to me) bonus is hidden inside the back cover – a CD with surveys of the six longest systems, a satellite view of the area with cave surveys superimposed, and an article describing the identification of two new species of bat.

You can buy one for £26 in Edinburgh – or. if you live further afield cost is £32.30 to include postage and packing within the UK. We will be using ‘caver mail’ as much as possible to reduce postal costs and keep cash back to fund the printing costs, and help towards production of volume two. Volume One is well worth the price and buyers are encouraged to contribute more as Gift Aid to help fund the next volume.

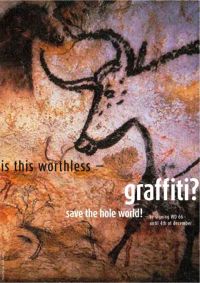

The France HABE Prize is awarded by the Department of Karst and the Cave Protection of the International Union of Speleology (UIS).

The France HABE Prize is awarded by the Department of Karst and the Cave Protection of the International Union of Speleology (UIS).

The Department of Geography and Geology at Western Kentucky University and its partners encourage you to participate in the summer 2014 Karst Field Studies Program at and near Mammoth Cave National Park . Tentative courses this summer will include:

The Department of Geography and Geology at Western Kentucky University and its partners encourage you to participate in the summer 2014 Karst Field Studies Program at and near Mammoth Cave National Park . Tentative courses this summer will include: The 22nd International Conference on Subterranean Biology will be held on 31 August to 5 September 2014 in Juriquilla, Querétaro, México.

The 22nd International Conference on Subterranean Biology will be held on 31 August to 5 September 2014 in Juriquilla, Querétaro, México.

Inside a cave in the municipality of Cocula, north of Chilpancingo, Guerrero, specialists of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) found a Mezcala type figurine and fragments of braziers that date back to the year 700 AD; in this same context, they found Olmec and pre Olmec ceramic which dates back to 1000 and 1200 BC, as well as osseous remains, which means this emptiness had different uses and was a place of funerary cult.

Inside a cave in the municipality of Cocula, north of Chilpancingo, Guerrero, specialists of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) found a Mezcala type figurine and fragments of braziers that date back to the year 700 AD; in this same context, they found Olmec and pre Olmec ceramic which dates back to 1000 and 1200 BC, as well as osseous remains, which means this emptiness had different uses and was a place of funerary cult. A cave littered with the bones of Ice Age creatures will open for the first time to the public on Saturday.

A cave littered with the bones of Ice Age creatures will open for the first time to the public on Saturday.